The job analysis study (aka practice analysis, job task analysis, role delineation) is typically the most expensive and least favorite of the test development activities, but it is absolutely foundational for the credentialing program’s quality and legal defensibility. The job analysis identifies the critical tasks, knowledge, and skills required for competent performance of the job role or profession being credentialed. The critical tasks, knowledge, and skills demonstrate the link between the content that will be measured on the examination and the actual job or job role being performed. Specifically, the job analysis:

Refers to the investigation of positions or job classes to obtain information about job duties and tasks, responsibilities, necessary worker characteristics (e.g., KSAs), working conditions, and/or other aspects of the work (AERA, APA, & NCME, 2014, p.220)

Why a Job Analysis Is a Must

Many credentialing programs wonder if the effort and cost of the job analysis study is really necessary. Couldn’t the process be abbreviated or skipped entirely? The risk of skipping this step or doing an inadequate study is enormous. Your program’s credibility in the marketplace is largely determined by how well candidates feel your exam matches and validates their personal experience in the profession or job role. For example, have you ever taken a credentialing exam and thought that much of it didn’t apply to your actual job? A properly conducted job analysis will help you pinpoint those aspects of the job role or profession that deserve focus, taken from the responses of your own candidates and credential holders, to ensure your exam product matches their experience. Creating an examination without doing this step often leads to failed programs, or sometimes, legal action against the credentialing body

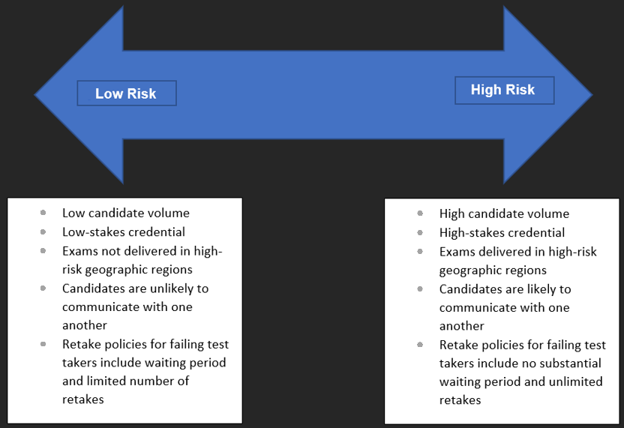

Without a properly conducted and documented job analysis study, the credential being created has no legal defensibility because it cannot be demonstrated that the credential is actually job related. Even with an extremely reliable or precise exam, if you cannot demonstrate a link back to competent job performance, you will lose a challenge to your examination in a U.S. court. Additionally, for highstakes credentials (e.g., those required to work, or those associated with promotions or pay increases), candidates are more likely, as a group, to search for any reason to challenge the examination in court, particularly if they do not pass.

A properly conducted job analysis study insulates your credentialing program from a wide majority of legal claims that can be made against your examination by directly linking the exam content to critical job tasks as well as by ensuring input from a demographically representative population of credential holders and others who are thoroughly knowledgeable of the credentialed job role or profession.

The first (and possibly the most important) step of a good job analysis study is recruiting the right group of SMEs. Most importantly, the SMEs must have a thorough understanding of the job role or profession being credentialed. As a group, the SMEs should be as representative as possible of all critical characteristics of the target audience for the credential (which typically requires between 8 and 12 SMEs). This means assembling a group that is ideally:

1. Geographically dispersed , or at least representative of your profession’s geographic practice areas. This is particularly important if you have practitioners across international boundaries that will be credentialed with the same exam. Regions with expected differences in practice based on location (e.g., legal frameworks) ought to be represented in your SME focus group.

2. Varied in terms of experience in the profession. Different specialties or work settings will bring varying views to the process that will help pinpoint exactly what is core to competent practice. This also applies to length of time in the profession, as it is a good idea to have both newer and more experienced members of the profession.

3. As diverse as possible in terms of other demographics, but particularly in protected class status (e.g., age, race, ethnicity, gender). Exams created under a singular societal lens will be more easily scrutinized, especially if the challenge is for disparate impact of results.

A Cautionary Tale

It can be tempting to assemble a group of SMEs based on convenience (e.g., most proximal, familiar SMEs), but there can be dire consequences of this approach. The following example illustrates this point:

The manager of an information technology certification was being pressured to complete a job analysis study and create a revised examination in a short time frame. In an effort to meet the timeline, he hurriedly scheduled a job analysis meeting and invited product owners/managers and others who had detailed knowledge of the product. He did not have a group that adequately understood the typical product user, and specifically the job role being credentialed. The result was an exam with questions that were too advanced and not relevant for the credential target audience. Candidates complained when the exam didn’t seem relevant and many failed to earn the credential. The job analysis study had to be redone and many of the items on the exam had to be replaced.

In this example, not only was time and money wasted in having to redo the job analysis and examination, but it hurt the credibility of the certification program.

It will likely require effort to recruit the right group of SMEs—the best and the brightest are often also the busiest—but it is well worth the effort to accomplish a more comprehensive study of the job role or profession, include diverse perspectives in deciding on examination content, and help to ensure the best representation possible of the job role or profession within your exam.

Job Analysis Steps

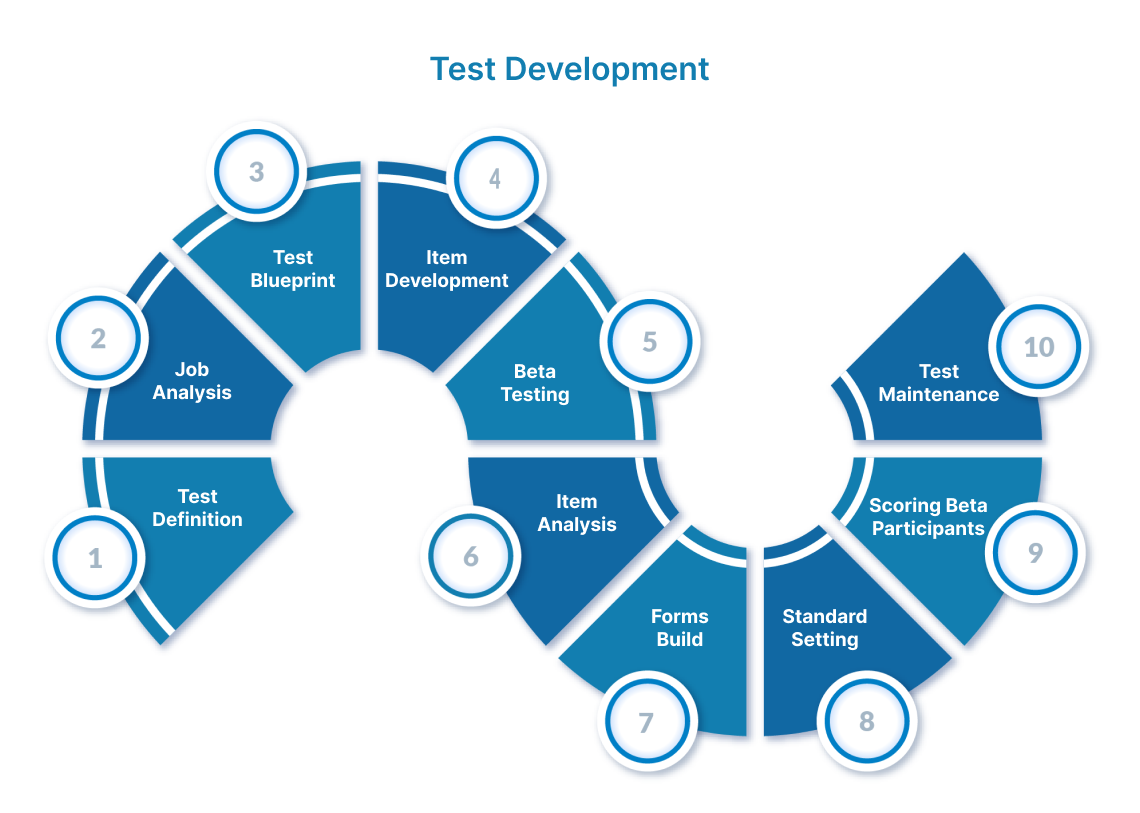

A job analysis study frequently takes three or four months to complete (and sometimes longer) and typically includes the following steps:

- Literature review to prepare for the job analysis meeting

- Meeting to develop the content for a job analysis survey

- Pilot testing and completion of the job analysis survey

- Survey administration to the target candidate population and data collection

- Data analysis of the survey results

- Meeting to review data results and determine examination content

As noted above, there is a lot of preparatory work that leads up to conducting a good job analysis study. During the literature review, the psychometrician gathers information from you, in addition to doing other research, to develop a broad picture of what the job role or profession entails in terms of work duties, tasks, skills, and underlying knowledge. This information is then compiled and presented to your group of SMEs who will review the content, make suggested additions, and remove irrelevant content from consideration.

The end goal of the process is to create a job analysis survey (containing a list of job-related content and some background information questions) to be distributed to a larger sample of the credential target audience

It is recommended that this job analysis meeting with your SMEs be held as a 2.5- day in-person meeting, as the process of creating the lists of tasks, knowledge, and skills can take considerable discussion to reach consensus among peers. If an in-person meeting is not feasible, this process can be done through a series of web conferences, but it will take much longer and frequently the quality of the work product is somewhat diminished compared to the work product of an in-person meeting.

Job Analysis Surveys

Once the content of the job analysis survey (i.e., tasks, knowledge, skills, and background information questions) is finalized, the survey is piloted with a small group of individuals in the credential target audience to look for any missing tasks, skills, or knowledge that may have been overlooked. Corrections are made after the pilot test. The survey is then distributed to the wider sample of the credential target audience. It is important to have a survey distribution plan that will allow you to obtain a sample that is adequately large and representative of the target audience.

The total number of completed surveys required depends on the size of your target audience, but frequently nearly 400 useable surveys are needed to adequately sample the total population.

If possible, it is helpful to have names and email addresses for survey recipients so that reminders can be customized and distributed to those who have not yet completed the survey.

In the job analysis survey, recipients are asked to rate the level of importance, frequency, and/or significance of each job-related task, knowledge, and skill to actual job performance. The purpose is to identify the primary tasks and supporting knowledge and skills expected of a credentialed individual. The results of a properly performed job analysis will provide data that illustrate the importance of individual job tasks, the frequency with which they are performed, and the importance of underlying knowledge and skills for competent performance. Because job analysis surveys tend to be lengthy, it is helpful to keep the survey open for at least three weeks and offer incentives for completing it (e.g., continuing education credits, prize drawing). If response rates are low, it may be necessary to extend the survey data collection period.

Once the survey data have been cleaned and analyzed by the psychometrician, the data then undergo a thorough review by your SMEs to ensure the results appear to represent expected performance, and the sample adequately represents the target audience as a whole. This review is typically conducted via web conference, and final data-driven decisions are made regarding whether each job task, knowledge, or skill should be included or excluded on the exam based on the survey data.

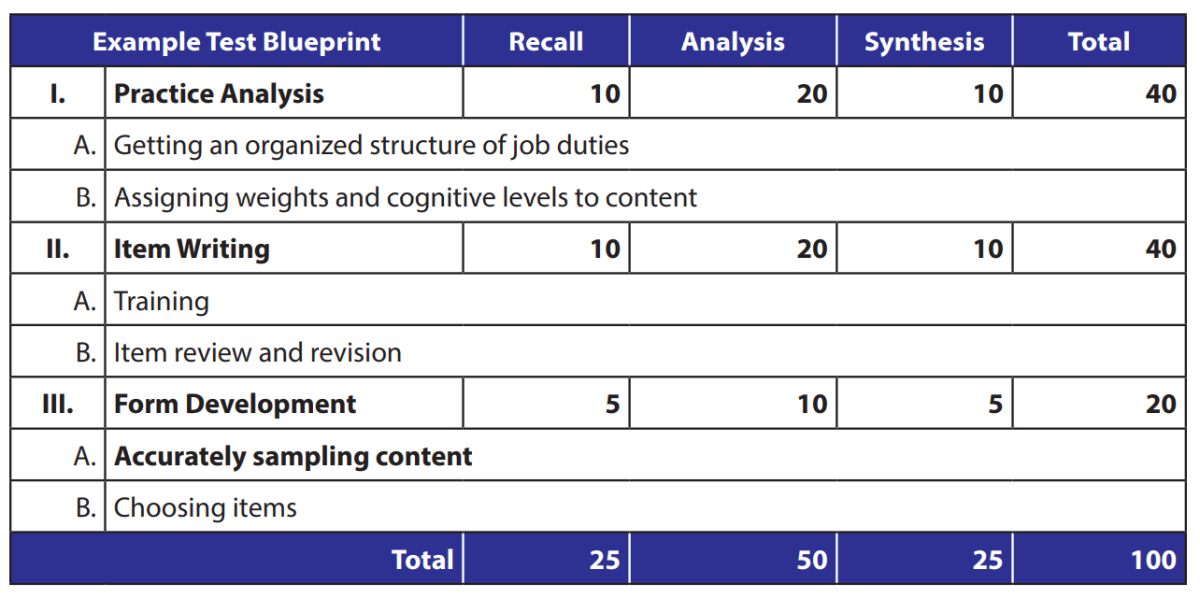

The important knowledge and skills that will be measured on the exam are linked to one or more important job tasks. In essence, this creates a list of job tasks that are widely performed throughout the target audience and are considered important for competent practice within the profession (i.e., they are valid) as well as a list of knowledge and skills deemed important for competent performance of the job tasks. The final list of content is the basis for a validated test blueprint. A good job analysis study will produce content for the test blueprint that informs what needs to be measured to demonstrate competence as well as to show how those things should be measured.